Morandi, in a conversation with American poet Edouard Roditi, says, ‘my only source of instruction has always been the study of works, whether of the past or contemporary artists, which can offer us an answer to our questions if we formulate these properly.’

He also insists he would ‘never be of much use as a guide or instructor’, though the irony is, much like his ‘source of instruction’ had been ‘the study of works, whether of the past or contemporary artists’, Morandi’s works are also great sources of instruction to so many artists today— myself included.

If you’ve read my newsletter on how I made Nightglow Moth, you’ll know that for every piece I create, there’s a secret painting that lies underneath the surface layer. And often, the underlayer happen to be a study* of a historical painting I love.

*Note: for those who are non-artist readers, an artist “study” is when you attempt to make a copy of an another’s work, with the intent of learning from their methods.

Wishing Tree, which is the piece I’m delving into today, started out as a Morandi study.

For most — I’m assuming Morandi too — studying the work of other artists is something separate from your art. Something you learn from on the sidelines of your main practice, before you switch gears and make your own stuff. But for me, the study is my work. It’s where my work begins. The first layer. The underpainting.

PART 1: The source

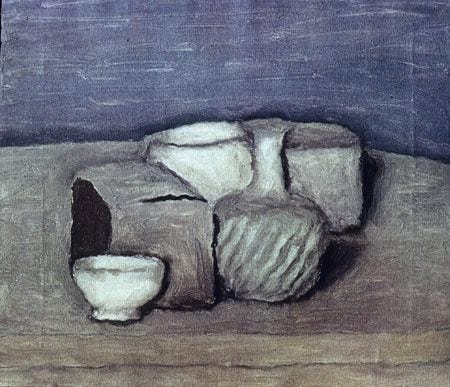

When I began copying this painting, I didn’t have any expectation of how I would transform it to make it my own. But after a particularly illuminating conversation with one of my tutors at the time, I realised that so much of Morandi’s still life paintings and etchings — if you squint — mirror the undulations, rhythms and balance of landscapes. Have a try with the image below:

This conversation sparked an idea: what if I painted a landscape on top of the Morandi study I had just made? How would Morandi’s still life, and my landscape be in dialogue together? This is where my investigation started.

PART 2: Naïve beginnings

The rough sketch below of the lone tree in a park was what I was aiming to layer on top of the Morandi study. Given how simple the drawing is, I thought it’d be a pretty easy painting to finish.

(It wasn’t.)

PART 3: The struggle became my technique

I discovered a word the other day, that perfectly describes my painting process (my “struggle” if you will): the word ‘Pentimento’ comes from the Italian ‘pentirsi’, meaning to repent, and describes a technique by which original drawn or painted elements (which are subsequently painted over/erased by the artist) peek through the final surface.

Initially, the Pentimento technique wasn’t a conscious thing I was trying to do. I was just really pedantic about how my paintings looked, so obsessively editing my work — layering, painting over bits I didn’t like/erasing, re-layering — became a natural part of my process.

Pentimento is something particularly prevalent in Wishing Tree — because for whatever reason, I couldn’t make the painting look right to me. I tried a lot of different things in an attempt to make it work: thick globs of colour. Thin glazes. Scratching into the surface. Staining. Throwing in pattern — like patchwork, dots, stripes.

I felt like I was going round in circles. At this stage I probably spent more time wiping away/concealing my “mistakes” than actually making progress.

In the end one, of my tutors suggested I take sandpaper to my work and go back a few steps, so eventually I could take steps forward again.

And it really helped.

PART 4: Sandpaper is a girl’s best friend

It’s a strange phenomenon that sanding your work lightly can make you see a painting with a lot more clarity.

For Wishing Tree, the clarity I received was realising that the orange in the lower 2 thirds of the painting and pale blue sky were competing with each other too much. I just needed to pick one dominant colour and run with it — so I unified the image with a wash of orange over the whole thing. That one move made a huge difference. Suddenly I felt like I was nearing the finishing line.

I knew at this point patience would be key. Any wrong turn would have put me 10 steps behind, so I put the piece away and turned to the thing that has always been a steady comfort in my life — books.

PART 5: The last clue

Leith School of Art has a wonderful collection of art books. I spent a good amount of time rifling through them during my year there. I loved looking at the works of Pierre Bonnard, Paul Klee, Victoria Crowe and Elizabeth Blackadder. But the artist that helped me finish Wishing Tree was French 19th century painter Edouard Vuillard (also a favourite!).

As I was leafing through a Vuillard catalogue, I stumbled upon his painting The Promenade.

Sometimes I like tracing outlines of paintings I enjoy, to learn why the composition works; The Promenade happened to be an image I traced outlines of. I pinned the tracings up on my studio wall, and in a matter of a couple weeks, the final puzzle piece of Wishing Tree jumped out at me; the two figures on the right of Vuillard’s painting were calling out to me…

…And a few details later — pale blue stripes to bring out the sky and dress, shading in the tree “wings”, an awkward flash of lemon yellow along the bottom — and I was done.

Finishing this piece was nothing but relief. It’s one of those rare pieces where I can look at it and confidently say that every battle I had with the paint was worth it. I think it makes the piece look weathered and textured, with all the histories of the painting peeking through to represent the passing of time. I often feel there’s something about Wishing Tree that feels nostalgic (but for what, I’m not quite sure).

It’s a most cherished piece, and the first painting I ever sold. I am so glad that it now belongs to a wonderful friend who did the painting course with me (hello if you’re reading — this newsletter is for you… if you care!)

There isn’t much else for me to say on this anymore, and so I’ll return to the Morandi quote I opened this email with:

‘My only source of instruction has always been the study of works, whether of the past or contemporary artists, which can offer us an answer to our questions if we formulate these properly...’

If Morandi had been my initial instruction, Vuillard was the answer to my final question. My guides! Guardian art angels perched on my shoulder!

In a way, everything I make is a love letter to the artists that came before me. Artists — and especially painters — endlessly inspire me. There won’t be a day I will ever be able to say that my paintings belong entirely to me. Because in truth, they belong to them.